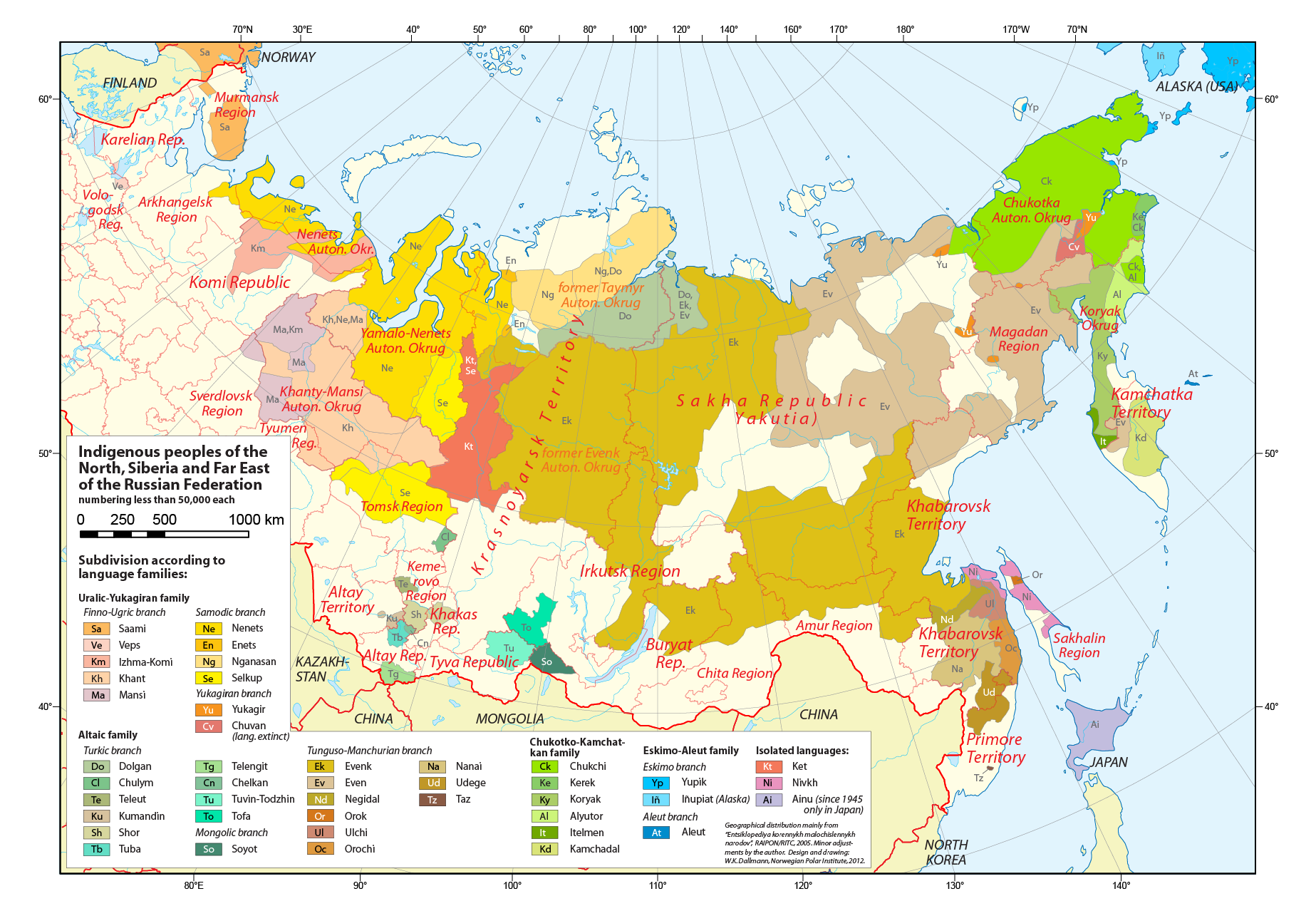

Photographer Sébastien Tixier grew up hearing tales of the Inuits in the polar regions from his father. Three years ago, and inspired by those stories, the Frenchman travelled to Greenland to see for himself the people who had piqued his curiosity since childhood.

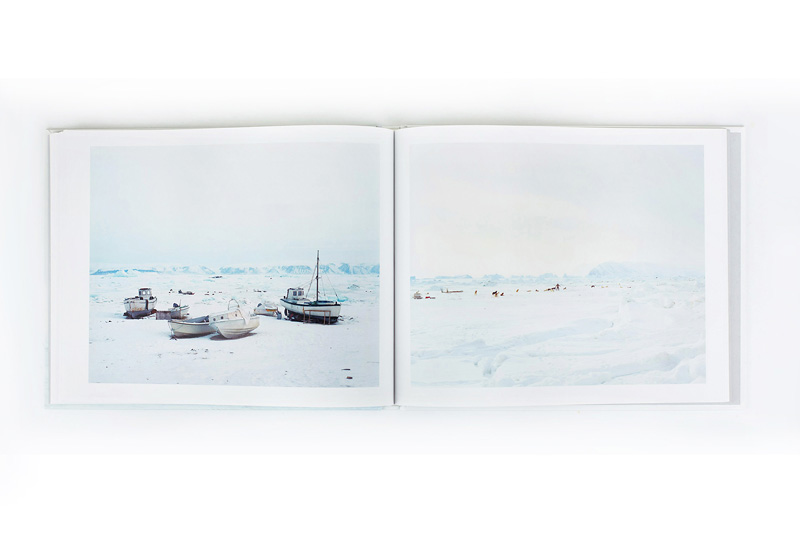

The result was Allangorpoq, the 35-year-old’s second published book of photographs. Translated from Greenlandic, the title means ‘being transformed’ and his project documents the changes taking place in the country’s society due to climate change, globalization and its embrace of western culture.

Based in Paris, Tixier has been working as a photographer for almost a decade and has also created bodies of work in Japan, Russia and France. His photographs have been exhibited throughout Europe and in America.

UpNorth’s Helen Wright spoke to Tixier about Allangorpoq and what he learned during the course of the project – and weather the country lived up to his childhood expectations.

Helen Wright: What made you want to go to Greenland?

Sébastien Tixier: I have always been fascinated with countries and settlements of the very north and especially Greenland, as I was told stories of the Inuits by my father when I was a child. As I documented this project, I looked at how the current reality is very different from the tales of my childhood.

The country is really at a crossroads. Its people have begun to embrace Western lifestyles and modes of consumption. Supermarkets and cell phones are making their way into the Inuit culture, and I wanted my work to capture how these rapid changes are raising questions about Inuit society and identity.

It was not just the landscape or icebergs, it really was documenting these transformations and questioning what they mean for both the environment and culture.

How did the project develop?

In mid-2011 I started the preparation process and this lasted about one and half years. It entailed comparing all the places I wanted to go, choosing the best season, making contacts in order to meet people, and learning the basis of Inuit language.

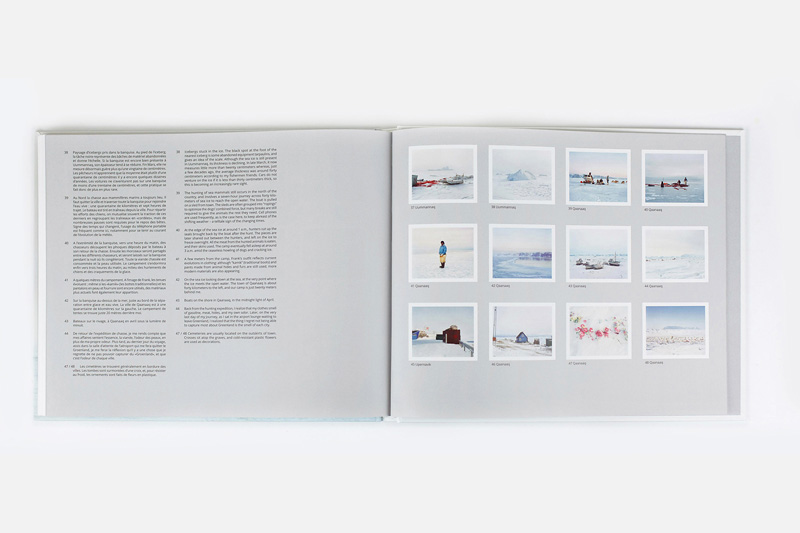

I went to Greenland in 2013, and then it took me another year to go through the editing process to produce the book, which was released in December 2014 / January 2015.

Did you travel all over Greenland or were you based in one place?

I travelled from some of Greenland’s “biggest” towns like Ilulissat, up to the northernmost town in Greenland (Qaanaaq, at the 77° north parallel).

In total, I picked four main regions for this project during the preparation process. I wanted to choose locations that would allow me to portray a variety of landscapes and ways of life across Greenland.

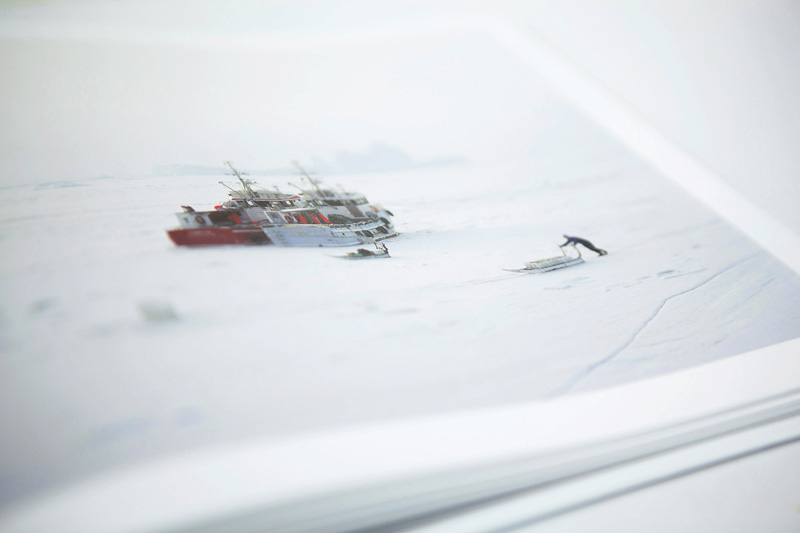

For example, the Qaaanaaq’s area, where I travelled for several days away from the town in sledge with hunters, offered a sharp contrast between the small town and life on the sea-ice. So the project includes four main regions with various locations in each of these regions as well as some places I traveled through on the way.

How long did you spent in the country?

Going to Greenland and especially some of the more remote places is very expensive. So I had a budget to stay for one-month. That was quite a short period, and consequently I had to prepare as much as I could before my departure to “optimize” my time for such a short stay and be able to take the pictures I needed. That’s why the preparation process was so long.

What made you interested in documenting the subject of climate change in Greenland?

The project is not “just” about climate change; I would say it’s more about the changes in general (“Allanngorpoq” can be translated into “being transformed” from Inuit language): the whole project is more about how Greenland’s society is changing in parallel of its environment. But speaking more precisely about the climate change, I think that everyone should be concerned. When associated to Greenland, the idea of “melting ice” and the risk of loosing it is quite striking.

How is Greenland changing? And how is this affecting the people who live there?

What was impressive to witness was the collision of both Inuit and Western cultures. In the “south”, towns have their housing projects in prefabricated buildings. Clothing made from animal hides are no longer used but at the very north for hunting trips – and yet they are mixed with more modern materials. And now even hunters at the very north in Qaanaaq are using Facebook, and yet some of their houses there don’t have running water.

Also in parallel, the environment changes have lead to changes in the habits or traditions: hunters in the north hardly reach the same location on the sea ice as they used to go before. This means they go to different hunting places which are less interesting for them.

But in this work and in the book I made of it, my intent as a photographer was more about asking the questions and raising awareness. I do not pretend to have the answers about what should be done.

And due to the changes you saw happening in the country have, or are any, traditions in danger of being lost?

Generally, my understanding was that most teenagers were turning away from continuing the traditional hunting activities, in persuit of dreams of higher studies.

In Uummannaq, the people who hosted me had also welcomed a little boy from the children’s home. When asked what he wanted to do as an adult, his answer was to become a wrestling superstar, as he had seen on MTV.

This sums up quite well the complexity of choices at work in Greenland today. And it is why I find it so fascinating.

Where you surprised by the changes you saw?

The first three days after my arrival in Greenland, there was simply no snow – at all. It was a great opportunity to document different aspects of the country at once, but was rather unexpected. I was also very surprised with how thin the sea ice can actually be. In Uummannaq, it was only about 20 centimeters. The locals told me that it used to be 40+ a decade ago.

What did the people who you met think of your project?

All the people that I’ve met were very welcoming and nice. Of course such a project evolves during the process, and for example, while I was thinking about making a book out of it, it was still quite uncertain at the time I was in Greenland. But I’ve had the pleasure to meet some very nice people who kindly told me about their lives in Greenland.

What format do you work with?

The series is shot on negative film using a medium format camera, the Mamiya RZ.

Are you happy with how the project turned out?

Sure! And making the book was an important milestone for me.

Did Greenland live up to your expectations? Are you planning to go back?

My only expectations were to discover the country, its environment and culture, and try to portray it. I feel totally happy and satisfied by how things turned out, and what I’ve learned from all points of view!

But, yes I still have this feeling that I’m not done yet with Greenland, but I don’t know when the next time I go back is going to be.