Estonia’s student resistance movement built a British NATO base in Estonia in 1982. And, of course, they wrote a song about it.

This week, Britain’s prime minister is heading to Ukraine, and the UK just announced that it is considering a range of new defense support for NATO nations along the eastern front, including sending an addition 1000 troops to strengthen NATO’s enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) in Estonia. The British forces-led eFP has added a new dimension to the deep relationship between the UK and Estonia. But for Estonians it also speaks to an element of historical nostalgia, reaching back into the days of the Soviet occupation and Estonia’s persistent cultural resistance throughout those 50 years. I think it’s time that our British friends understood exactly how significant their presence on Estonian soil is.

Since 1919 — when Britain sent a Royal Navy squadron to Tallinn during Estonia’s War of Independence, when Estonia fought invading Bolshevist Russian forces — Estonians have almost instinctively thought of Britain as its natural ally. In 1919-20, the British Navy kept naval supply lines open and supported the fledgling Estonian navy. This helped Estonia field massive ground forces to push back the Russians and bring victory, a peace treaty, and 20 years of independence.

In 1939, under the auspices of the infamous Hitler-Stalin pact, the Soviet Union forcibly established military bases again in Estonia. In 1940, they broke the peace treaty, occupied and annexed Estonia into the Soviet Union, and began a massive Stalinization campaign. Most of Estonia’s political leadership was deported and murdered; the military was subdued; and our constitutional institutions were liquidated.

The Soviet Union and Nazi Germany were military allies. They had divided Poland, and Stalin invaded Finland. Estonia was, in practice, considered “gone” by the outside world — just like Crimea is now. And just like with Crimea, democratic Western powers refused to recognize the Russian capture of the Baltic States.

In 1941, the Germans violated the Hitler-Stalin pact and invaded the Soviet Union. Estonia’s Soviet occupation was replaced by a Nazi occupation, and Estonia was then sandwiched and suppressed between two of its arch-enemies. The national resistance movement that gained ground under the Nazi occupation of 1941-44 aimed to restore national independence after the war — with the help of Western powers. In the Atlantic Charter of August 1941, Roosevelt and Churchill declared that they “[wished] to see sovereign rights and self government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them.” This was the promise that directed Estonia’s fight for the restoration of it independence for the next 50 years.

The Estonian Embassy in London continued to function despite Soviet demands to hand it over. The underground Estonian National Committee was formed in 1944 when Nazi-occupied Estonia declared its intent to re-establish a democratic government, in alliance with the Western Powers, after the war. In spring 1944, Estonians fought against the invading Soviet army, and in the fall of 1944 against the departing German army. The interim government, headed by Otto Tief, asked for British observers and mediation with the Russians to get then to recognize Estonian independence. To no avail. The Russians were too strong; Stalin could demand more than Britain and America could push back.

Estonia was reoccupied, and the remnants of Estonian units from different armies regrouped in forests to fight an isolated and proud guerrilla war against the occupier that lasted eight bloody years. Churchill’s Fulton speech in 1946, in which he declared an Iron Curtain has descended across the continent of Europe, was widely spread among Forest Brother units as evidence that Estonia had not been forgotten.

Urban legends of liberating British paratroopers allegedly sighted in Estonia, stories about British submarines reaching Estonian shores, and a slow-to-dwindle belief in an immediate war of democracies against the Soviet Union kept Estonian spirit alive for decades.

“The White Ship” — the ship of a liberating British navy — became a motif of resistance songs — and soon too of fairy tales. Years passed. The last Forest Brothers were killed in the 1970s. And Estonians still waited for the white ship. They never lost hope that “one day, we will win.”

The bloody forest wars of the 1940s and 50s were taken over by the Estonian dissident movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s. The second generation of Estonian resistance concentrated on fighting for the right of speech and the right of self-determination; they fought with appeals to the United Nations, and through a struggle to keep the culture, language, arts and, spirit of the Estonian nation intact. Not many people in London and Washington thought that Estonia would ever see independence again. Not so in Estonia.

By the early 1980s, the third generation of Estonian resistance started to take over. Young Estonians — whose fathers had spent years in Soviet gulags, but who did not have the first-hand experience of mass repression — began to organize. In the fall of 1980, Estonia saw its first anti-occupation political rallies with hundreds of mostly teenage participants. Four hundred people were arrested. This had not happened for decades.

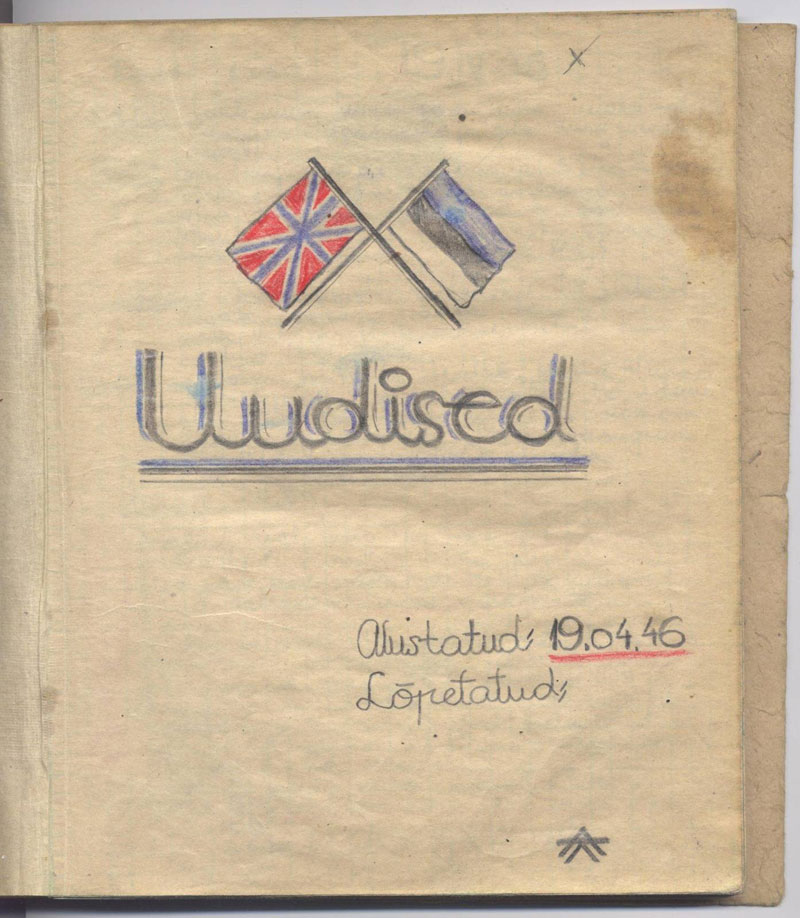

The student movement started to organize itself through semi-official networks. One of these was the so-called “Estonian Students Construction Camp” (EÜE) initiative. Officially — and formally under the auspices of Komsomol — Estonian students organized into summer camps to help the Soviet economy by contributing cheap labor. Dozens of groups of students spent a few months each summer at remote locations in the countryside, to build a barn or work in collectivized agriculture or some other such activity. Relatively unsupervised, these groups essentially became cells of resistance. A cross-country network developed that was later deployed in the independence movement. An interesting EÜE subculture with its own songs, codes and traditions developed.

In the summer of 1982, one of these EÜE groups — about 30 people, mostly students from Tartu University and Tallinn Technical University — was sent to Tilsi, in south Estonia. Officially, they were there to learn “soviet work ethics.” (Tilsi, by the way, was about 25 kilometers from the Soviet nuclear missile base in Nursi. As we know now, the Soviets had eight nuclear war heads in missiles ready to launch in Võru county alone.)

The core of the Tilsi group had spent the previous summer in a similar camp — and used the time to mock the Stalinist era of the Soviet Union. They had called their group Persostrat, a Soviet abbreviation for pervõi sovetskii stratostat (First Soviet Stratostate) — an idiotic Soviet term which in Estonian sounds a lot like “ass sphere.” One of the songs that the group wrote that summer was called “Stalin is a hundred years old” — no matter that Stalin’s 100th birthday had been in 1978.

In 1982, the group initially planned to dedicate the summer to making fun of the next Soviet idiocy — the maize (corn) growing campaign of Khrushchev, and the outrageous (and admittedly funny) propaganda campaign that had accompanied it. Thus the group was called Euromais (for European corn) in mockery of the Soviet fashion of weird abbreviations.

But after gathering, the group’s leader, Mati Laur, came up with a different plan. “Enough of this Soviet shit,” he said. So instead of becoming a parody of a Soviet campaign, the students decided to become something even better. The decision was taken to become a NATO base in Estonia. More specifically, a British NATO base in Estonia.

Why British? Anything British was, by tradition, considered the most anti-Soviet tradition. The British navy in Tallinn in 1919, the hope for a White Ship, and the recent Falklands War — led by then wildly popular Margaret Thatcher — played a role in the decision. Thatcher and Reagan were probably never as popular in their homelands as they were among young Estonians in their occupied homeland in the 1980s.

So Euromais, despite its name, became a “NATO base,” complete with English-language signs, a strict schedule, afternoon tea, picnics, proper table manners, and a sense of superiority towards anything Soviet. Back then — like it is more and more again — Soviet meant Russian.

The NATO base needed a song, it was decided, and soon, out of collective effort, a song was born. A song that even today is still sung at student gatherings all over the country.

The choice of melody was not British but American (to also keep our American friends in mind). It was set to the tune of “Yankee Doodle” — an obscure choice at first glance, but a deeply symbolic one beyond the Iron Curtain. The American radio broadcasts for the captive nations, known as the Voice of America, had been listened to in most households since they had begun in 1951. “Yankee Doodle” was used as the call-sign of the VOA Estonian program. The broadcast itself was usually jammed by the Soviet jammers — but the call-sign itself usually got through before the jamming, and it was known to literally everyone in Estonia.

Lyrics were assembled as collective effort. The fist version was written by Mati Laur, now a history professor at Tartu University; Lauri Vahtre, a historian and politician, and a member of parliament after the restoration of independence; and Sulev Kannike added a few verses. Kannike is now a diplomat. Ironically, he became Estonia’s Ambassador to NATO, and held that post when Estonia joined the Alliance in 2004.

The song is printed below. The lyrics have layers of references to international events unfolding in 1982, which are commented on in the footnotes after the song. For example, it is hard to explain today why Pinochet is included in the refrain with Reagan and Thatcher. But let’s just say that in 1982, for we Estonian students, Pinochet was someone fighting the communists and for us, that meant he was a friend. But let Pravda have fun with that.

The final verse was added a few years later, probably in 1984, when some of the students returned from their two-year term as conscripts in the Soviet army. For them it was now clear that the Soviet system, with this clunky conscript army they had just seen, could not last. And that NATO, finally, would come.

So this is the story of this one song — one Estonian song in a sea of songs of patriotism and protest that helped preserve Estonian identity and culture throughout the occupation, and carried us forward to the Singing Revolution and the restoration of our independence — and I do hope that the new British troops — due to arrive shortly in Estonia — find time to take it into their own repertoire.

(The translation provided is as close to the original as possible while maintaining meter and rhyme. The content is all there, and the attitude is translated fully.)

An Estonian rendition of Yankee Doodle, to dedicate a NATO base in Estonia in 1982

Our enemies have bloody hands

every fourth one, a killer

They roam all ’round the Russian lands

bombs in their sacks as filler

Refrain:

Students of Estonia [1]

a NATO crew united

Whom Reagan, Thatcher, Pinochet

greet home all so delighted

The junta man with epaulets

is raging ‘round in Poland [2]

A Cuban warlord dark as night

cuts palm trees in Angola [3]

[Refr: Students of Estonia …]

But we still hold North Irish shores

Hong Kong and then Guayana

We’ll always have Port Stanley too

Leave Falklands — never gonna! [4]

[Refr: Students of Estonia …]

Piss off you greedy Muscovite

your neck will now be broken

By royal lion, unicorn

Welsh Dragon you’ve awoken

[Refr: Students of Estonia …]

When Russkie bear, so furious

will reach the English Channel

God saves this land so glorious[5]

and tames the savage mammal

[Refr: Students of Estonia …]

When picnic ours at Satterfield [6]

hears news about the battle

I push aside my porcelain

drink whiskey from the bottle

[Refr: Students of Estonia …]

And when victorious NATO troops

have liberated Tallinn

Humiliated Russian crooks

towards Narva will be runnin’!

[Refr: Students of Estonia …]

[1] The Estonian original is “EÜE and Euromais”, obviously not singable in English

[2] A reference to Jaruzelsky and martial law in Poland — and the Solidarity movement.

[3] Cuban communist forces in Angolan civil war cutting trees to build bunkers

[4] Obviously the Falkland war that had ended in June 1982

[5] This line is sung standing as an anthem, and slowly. In the Estonian original: “Then God protects England”

[6] Satterfield is a fictional place for Euromais, an imagined British ideal. “You are invited to the Satterfield palace for picnic” was a code phrase to a Euromais gathering etc