The first part of a two part series looking at the history of US-Baltic diplomatic relations over two centuries.

Part two is available here.

Part I: First Contact

As a historian, one of the stranger hobbies I have had over the years is visiting historic cemeteries and graves around the world. Many of them are places of beauty, fantastic locales for a stroll (or hike, to be frank, as many are very hilly and large) such as Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, Zentralfriedhof in Vienna, or Metsakalmistu in Tallinn. But when you know the histories of the individuals resting in those picturesque locations, it makes the trek even more fascinating.

Of course I have visited some of the most historic of cemeteries around the world and key individuals in the course of world history, from President Lincoln in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield to Admiral Togo in Tama Cemetery in Tokyo, from General Marshall in Arlington National Cemetery to Václav Havel in Vinohrad Cemetery in Prague, the list goes on. On the other hand, I also took journeys to far-flung communities to track down single, significant graves in small, rural communities — just to feel history first hand.

A few years ago during these journeys I took it upon myself to visit the graves of figures I consider heroic, but largely forgotten in history, to the Baltic region. Having devoted myself to the Baltics my entire life, I sought out those who had done so much for this region during the Interwar period, especially those who played a major role in giving these three small countries a chance to survive in those turbulent early years when war was coming at all fronts. The more research I did, the more I saw how many other fellow Americans devoted themselves to these three little countries so far away, and I wanted to pay respect to them. This became a personal journey.

The more research I did, the more I discovered the small but certain connections between the United States and the Baltic region. For this and so much of this article I am thankful for the work done by the US State Department’s historians, who did most of the heavy lifting; however, much of the cemetery question – from research to discovery to visit – were done personally.

The Earliest Americans in the Baltics

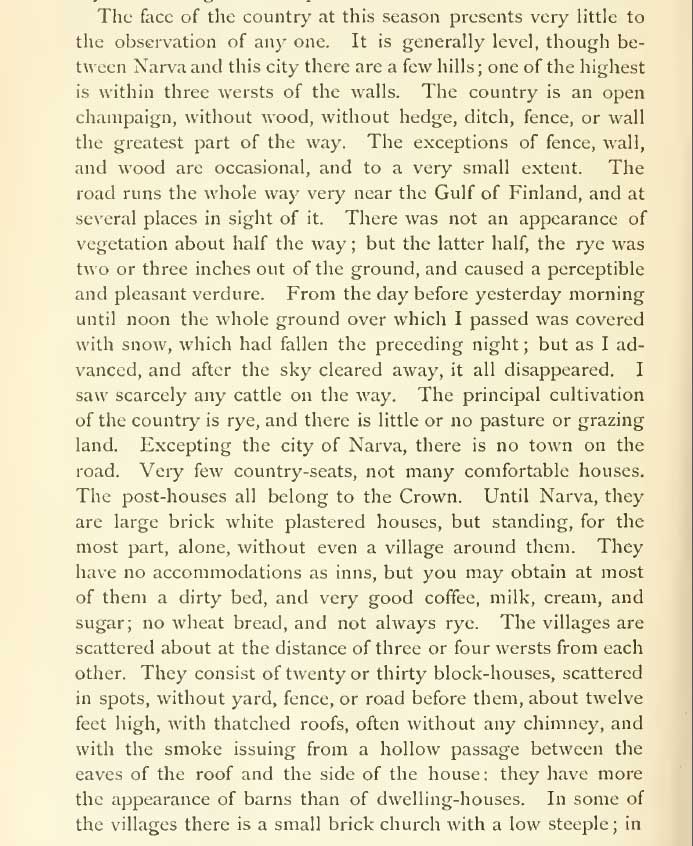

Even as far back as the start of the 19th century, the outgoing US Minister to Russia, the future Secretary of State and President, John Quincy Adams, visited Reval (Tallinn) for several days to sort out a diplomatic dispute arising from the effects of the ongoing War of 1812 (he would later be a chief negotiator for the Treaty of Ghent which ended the war). He is, of course entombed in Quincy next to his illustrious father. His descriptions of church services at Toomkirik were amongst the very first such accounts of an American in Estonia.

There were rudimentary US consular missions in the region during parts of the 1800s, especially during the Civil War period to ensure vigilance over Confederate activities on recognition, trade, etc. I unfortunately have not been able to track down much info on the individuals who served as US consul to Reval during this period, such as Charles Leas (of Baltimore) and Henry Stacey (of Vermont, who died in Tallinn, was buried in Kopli before being repatriated to the US to an unknown location) before the downsizing of US foreign representations during the scandal-plagued Grant Administration. Eugene Schuyler served as the final Consul in Reval for that short period in 1869-1870 before closing the office on Narva road, moving to take over as Consul in St Petersburg. Schuyler was an incredibly well-educated individual, having translated Turgenev’s Father and Sons, and even edited an early translation of Kalevala. After his short Estonia posting, he became one of the first Americans to explore Central Asia before a long career in diplomacy; his role in describing Ottoman atrocities against Bulgarians led directly to the war that liberated Bulgaria — which, unsurprisingly led to an angry Constantinople to demand his expulsion. He died from malaria contracted during his later posting in Cairo, and is buried on the historic cemetery island of San Michele in Venice.

Not until 1919 would a US representative return to the region. Although the Wilson Administration had not recognised Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania de jure, this de facto appointment brought John Allyne Gade (of New York) to Riga. Gade, already a well-known figure in navy intelligence and relief efforts, having worked with the tireless Herbert Hoover on many of them through World War I, was sent as Commissioner to the Baltics. Secretary of State Robert Lansing, a visionary in the murky world of intelligence, ostensibly sent Gade to keep an eye out on Soviet Russia and its activities as the Baltic states were all mired in wars of independence at the time (Lansing’s nephew-in-law, Allen Welsh Dulles, would later become an intelligence pioneer and CIA Director).

Gade played a significant role during his short stint in the Baltics, earning honours for not just his public role as head of the US mission to the region, but as an advocate in the background. Before departing in 1920 after peace was achieved in Estonia and Latvia, he advocated for permanent US representation — despite the lack of de jure recognition.

Gade continued a long career in banking, military and diplomacy, and died in 1955. Unfortunately, I was unable to find any of his burial information, despite his storied career. He was succeeded in Riga by Evan Young (of South Dakota), who became the first Minister when the Harding Administration recognised the three Baltic states de jure in 1922.

The “Other” Enemy of Baltic Independence

With World War I in full force, one of the horrors of that cataclysmic war was the plagues of hunger and disease. Even before the entry of the US into the war, some took it upon themselves to act.

One of the principle individuals of this effort was future President Herbert Hoover, who started the Commission for Relief in Belgium. This noble, volunteer effort faced opposition from the occupying Germans and from Britain, who thought this was enabling the occupation. Nevertheless it saved countless lives. This led to the creation of the US Food Administration when the US entered the war, with Hoover directing the efforts to distribute food. After the armistice that ended the war, it evolved into the American Relief Administration, which played an enormous role in helping Poland, the Baltic countries and Russia to survive post-war famines.

But the real crisis for the Baltic countries, alongside many others, was the scourge of disease. Typhus was a major problem all over Europe, and claimed countless lives as it spread in those pre-vaccination days. The Red Cross sprung into action, alongside many volunteers, and stemmed the spread of the disease all over the continent, again saving countless lives. Many of these volunteers risked their own lives, as they themselves were exposed to typhus.

One heroic individual, sadly lost to history, was Doctor Edward William Ryan. A courageous soul who constantly volunteered around the world to aid those caught up in conflict, he first volunteered to help evacuate Americans caught up in the Mexican Revolution. With World War I raging, the American Red Cross sought volunteers to help with relief efforts in Europe, and Dr Ryan quickly signed up to help in Serbia. Many credit him for saving Belgrade from the onslaught of the Habsburg forces, and is recognised by Serbia as a hero. He risked his own life in the typhus epidemic there, and despite nearly dying from it, saved thousands of lives running the ARC hospital there.

When the US entered the conflict, he was given a military commission by the US Army, and he continued his work on the front lines in France and Greece. At the end of the war, he continued his work in Berlin until fate took him to Estonia in 1919. Concerned by what he saw in the Estonian War of Independence, he helped to create and lead the American Red Cross Commission to Western Russia and the Baltic States.

Dr Ryan, with his deputy Loy Henderson (more on him later) who he recruited at the time, travelled through the region in the midst of several wars of independence, setting up ARC offices from Kaunas to Helsinki. During the worst of the typhus epidemic in Estonia, Dr Ryan took charge of the efforts in Tallinn, often butting heads with the government. But the widely-respected Dr Ryan managed the situation, with Henderson leading the same efforts in Narva at the front lines, at the massive field hospitals set up at Narva and Ivangorod/Jaanilinn castles. When the White Army of General Yudenich pushed deep into Red Russian territory, Dr Ryan followed, running Red Cross units in western Russia.

During this time, two American soldiers working with the ARC in Estonia lost their lives to typhus, which Henderson also nearly died from. Both men, Lieutenant Clifford Arthur Blanton and George W Winfield, were first buried at Tallinn’s Sõjakalmistu in 1920 but repatriated home; Blanton is buried in Forest Hills Cemetery in Chattanooga (sadly I could not locate the flat marker, listing his place of death as “Narva, Esthonia” during my visit); for Winfield I have not found any information.

What became a remarkable side story, is how Dr Ryan travelled with the Estonian delegation to negotiate the Tartu Peace Treaty in early 1920. His unauthorised trip angered Commissioner Gade, but his first-hand information on the state of Soviet Russia was so negative that his report likely played a role in the decision of Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby to not recognise Soviet Russia. Commissioner Gade would write in his memoirs:

“Ryan proved himself to be a wild, fighting Irishman, constantly getting himself into hot water and me into a state of exasperation, doing things which I highly disapproved, even going to Moscow despite my having forbidden it. Absolutely fearless, often gambling with death, he did a grand job of holding high the shining fame of American charity.”

Dr Ryan remained in the Baltics until 1922, springing into action wherever a hotspot appeared that required his energy and dedication. Henderson, mourning the loss of his twin brother, had shifted to the Berlin office to co-ordinate regional efforts from there. He was honoured by the Baltic-American Society upon returning home, just as the Harding Administration officially recognised the three Baltic states.

Sadly, the restless Dr Ryan did not survive his final posting, having volunteered to help battle disease in Tehran. He died there, succumbing to disease at the young age of 39, and was buried in his home town of Scranton. Ants Piip, who was the Riigivanem who at times butted heads with Dr Ryan during the typhus epidemic of 1920, happened to be the Estonian Minister to the United States at the time, and made his way to St Peter’s Cathedral to pay his respects.

I managed to find Dr Ryan’s beautiful grave at Scranton’s Cathedral Cemetery thanks to the help of a wonderful staff member — despite the cemetery’s loss of records from that era. Turns out it was very close to the entrance gate. Again, a beautiful stone for a hero of Estonia and so many other countries. I was humbled to have stood in his presence.

As for his protégé, Loy Henderson, his career had just started. He went on to be a principle figure in US diplomacy, returning to the Baltics in 1924 to work in the legation in Riga. He managed to work in all 3 Baltic embassies, going first to Kaunas in 1927 and then to Tallinn in 1930. Then alongside a few junior officers in the Baltics such as George Kennan and Charles Bohlen, he helped open the US Embassy in Moscow under Ambassador William Bullitt. For a short time as charge d’affaires, Henderson warned the State Department about collusion between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, but the warnings were unheeded.

When the Soviet Union occupied the Baltic states, Henderson was considered the principle drafter of the Welles Declaration. In fact, his anger over Soviet activities clashed with the Roosevelt Administration upon Moscow turning into a war ally he asked to be transferred out of European affairs within the State Department, and was given the post of Minister to Iraq in 1943. He would later serve as Ambassador to India and Iran, ironically in the same city where his mentor lost his life 30 years earlier. In his time as a Middle East specialist, he warned about Moscow’s links with Syria — something we are dealing with decades later. Henderson also likely had a hand in the CIA-led coup in Iran while he was posted there.

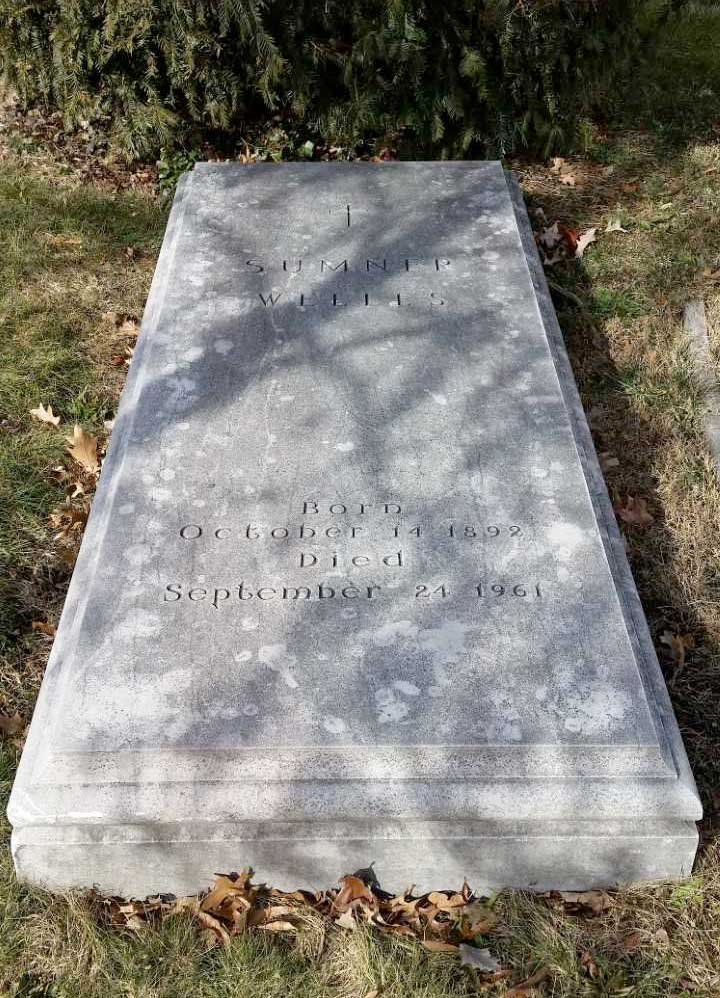

Henderson is buried at Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington DC, in a section that is the resting place for dozens of US diplomats; unfortunately my photo is blighted by sunlight, requiring me to re-visit one day. He is not buried far from Latvia’s Ambassador Anatols Dinbergs (and the entire Latvian section), nor far away from Sumner Welles — whose historic declaration he helped to draft. For a historian, this is one of the most interesting cemeteries; buried here are several cabinet members, scores of politicians and generals, writers like Gore Vidal, Supreme Court justices, Russian nobles, KGB defectors — and of course Upton Sinclair, whose infamous novel The Jungle featured a Lithuanian immigrants as the main character.

A sad side note to this story is the fate of Sumner Welles, who was caught up in the ugly situations that DC rivalries can create. As Undersecretary of State under Cordell Hull, both men sought the attention of their boss President Roosevelt. Hull, despite his illness, was continuously unhappy with Welles’s access to FDR. When Welles was caught in what is still suspected as a honey trap, Hull sent his friend William Bullitt (Henderson’s boss in Moscow) to leak the hushed-up story to Klan-supported, Maine Senator Owen Brewster (in the Martin Scorsese film The Aviator he is played by Alan Alda), which pressured Welles to resign. He was replaced by Edward Stettinius, who became Secretary of State after Hull died a few months later (entombed at the National Cathedral); Stettinius was later criticised for pushing FDR to concede too much to Stalin at Yalta. Ironically, where Stettinius is buried (Locust Valley Cemetery on Long Island, one of the most beautiful cemeteries in the country) is where a lot of Latvian Americans are buried. Bullitt is buried in The Woodlands Cemetery next to the University of Pennsylvania, and Brewster is buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery in the central Maine town of Dexter.

The Early US Diplomats

As mentioned earlier John Gade was the first Commissioner to the Baltics, succeeded by Evan Young — who would become the first Minister upon de jure recognition. During that time, other US diplomats played significant roles in setting things up as the minister was based in Riga full-time.

The US Consulate in Tallinn was first opened in 1919 by John Patrick Hurley (of New York). A decorated soldier who fought in units under Generals “Wild Bill” Donovan (father of the OSS) and Douglas MacArthur, he was charged with setting up the consulate by Commissioner Gade; ironically, the location of the first US Consulate is today where the Russian Embassy is located in Tallinn’s Old Town. He switched to become US Consul in Riga until 1924, becoming one of the longest early American residents of Riga. He had a long career in foreign service, and is best known for his heroic work in helping evacuate those trapped in Marseille in 1940 where he was US Consul. He was replaced in Tallinn in 1920 by Charles Albrecht (of Pennsylvania) for the next 2 years. Unfortunately I have not been able to find the final resting places of these individuals.

One of the non-diplomatic advocates for the recognition of the Baltics in the meantime came in the form of Congressman Walter Chandler of New York. The progressive from Manahttan was defeated in his quest for a 4th term in 1918, which gave him the opportunity to travel to assess the post-war situation in Europe. He became the first former US congressman to visit the newly-independent countries, despite the wars of independence raging. He returned to Washington and became a vocal advocate for the recognition of the Baltic countries, testifying at House hearings that sadly proved futile at the time. He returned to the House in 1920 to serve one last term, but spent time in the Baltics before then. He continued to lobby on behalf of the Baltics, his speeches can be read in the Congressional Record. He pushed the Harding Administration as well, lobbying with Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, and finally succeeded when the recognitions came in July 1922. Unfortunately, Chandler lost re-election later that year to the legendary Sol Bloom, who would hold the seat for the next 25 years. Chandler, the best friend of the Baltics in the US Congress of the era, died in 1935 and is buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Jacksonville. I was unsuccessful in locating his marker during a previous visit to the sprawling cemetery, fighting the intense heat and humidity, endless bugs, and a severely sprained ankle (yes, cemetery trekking can be dangerous!). No doubt I will return one day to pay my respects to this great individual.

Also mentioned earlier, with US recognition of the three Baltic states in 1922 during the Harding Administration, Commissioner Young was upgraded to that of Minister to all three countries; however, this role was temporary as the State Department under Hughes (buried at the historic Woodland Cemetery in the Bronx) sent a new team to the newly-recognised countries.

Hughes in September 1922 sent Frederick Coleman to be Minister to all three Baltic countries. Little did anyone know at the time Coleman would serve three administrations (Harding, Coolidge, Hoover) in this capacity, staying in Riga until his 1931 departure. His extremely long, nine-year tenure saw the Baltics grow very quickly, but also witnessed them experience major challenges such as the 1924 attempted Soviet coup in Estonia, the 1926 move to authoritarianism in Lithuania, and of course the Great Depression. Few outsiders saw so much of Riga and its dramatic changes during this turbulent but exciting period of the nation’s early history.

As Coleman resided in Riga yet was accredited to all three countries, Tallinn and Kaunas (remember, Vilnius was occupied and annexed to Poland at the time) were served by consulates. Various individuals ran the consulates during the period until 1930, when both were upgraded to full legations, and the residing consuls were deemed charges d’affaires.

The heavily decorated Coleman departed from Riga in 1931 and was given a recess appointment as Minister to Denmark. Though he was later confirmed by the Senate, he only presented his credentials in early 1932 and served for just one year due to President Hoover’s loss to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. I didn’t manage to find much info of his post-Copenhagen life, but Coleman passed in 1947. I have not managed to find his final resting place, though the search is taking me to the Carolinas at this point.

While Coleman served as Minister in Riga for nine years, little did he know that when Harry Edwin Carlson arrived in Tallinn in August 1926 as Consul he would surpass that longevity mark. Carlson would remain in Estonia as Consul and charge d’affaires (after the legation’s upgrade in 1930) until 1937; few, if any, Americans had lived in Estonia for so long during this era.

Carlson had already been Consul in Kaunas since 1924 before he was transferred to Tallinn. During his 11-year tenure in Estonia, Carlson saw Estonia experience the Great Depression, the rapid recovery, the Päts takeover, and the country’s continual growth despite the unsettling international environment. They played significant roles in society; together with his wife Laura, Carlson made the most of his Estonian life. They constantly travelled around the country, owning a suvila in Haapsalu, and Carlson was known for his love of fishing. He helped to found the Rotary Club, and Laura was instrumental in making the now-famous 1939 feature article in National Geographic happen. Carlson was also responsible for moving the legation to Kentmanni, where the current US Embassy is located.

After this long, storied time in Tallinn, Carlson went to London as Consul. No doubt, he played a role in suggesting to the son of the then-ambassador, Joseph Kennedy, to visit Estonia — future President John F Kennedy. Ironically one of the critics of the visits was one of the diplomats working under Carlson in Tallinn, the legendary George Kennan. Carlson then had the difficult job of serving as US Consul in post-Anschluss Vienna, serving from 1939 until the US declaration of war against Nazi Germany in 1941. Carlson then served a very important posting as Consul in Stockholm for the duration of the war, where no doubt he had re-connected with his Estonian friends who had fled. After several more postings he retired, and passed in 1960; Laura would pass in 1978.

Both are buried in the small Berkshires town of Sheffield, Massachusetts. Though the cemetery is not very big, their small markers were not easy to find on a sunny late afternoon. My zeal to pay my respect to them took me from stone to stone, crossing the entire cemetery. About half an hour later, I found the stones, against the edge in the back section. I stood there for ten minutes, thinking that they didn’t get to see Estonia proud and free and successful again. But later I would learn that one of their two children, both born in Estonia by the way, would marry a Latvian American.

As mentioned earlier, the legendary George Kennan had worked in the legation in Tallinn under Carlson for a short time before moving onto Riga to work there until 1933. Kennan had then, under Bullitt and Loy Henderson, worked in the new Embassy in Moscow. Kennan treated Carlson rather harshly in his memoirs, though part of the tension is likely due to career paths — Carlson enjoyed his Estonia time, Kennan used it as a springboard to his desired Russia posting. Kennan of course became a legend in dealing with the Soviet Union, becoming Ambassador before being expelled by Moscow. Kennan is buried in Princeton Cemetery, not far from President Grover Cleveland, Vice President Aaron Burr, and scores of other famous individuals.

Working under Carlson in Tallinn was also Charles Eustis Bohlen, who joined the team under Bullitt in the Moscow Embassy. Bohlen was likely the first US diplomat to get his hands on the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact’s texts — including the secret protocols — leaked by a German diplomat. Bohlen followed Kennan as Ambassador in Moscow before becoming Ambassador to France — like his grandfather James Eustis. He is buried in his family plot at the historic Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, and his daughter continues the family tradition working as career diplomats. His brother-in-law was Charles Thayer, who ran VOA in 1948-49 but often seen as being soft on Soviet dominance like Bohlen — something that led to the latter’s falling out with his mentor Kennan.