Listen to Finland. And to Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland; to Czechs and Slovaks; to Belarussians, Hungarians, Ukrainians, Tatars and others. That is how Westerners should be commemorating the 70th anniversary of the Nazi capitulation. These countries—the places that the great Yale historian Timothy Snyder calls the “Bloodlands”—were the victims of aggression and mass murder. Some of them suffered national obliteration and decades of foreign occupation.

These countries and peoples did not start the war. They did not ignore and appease German revanchism. They did not elect dictators or do deals with Stalin. But they bore the brunt of the consequences.

Yet their voices are rarely heard in the discussion about the modern meaning of the Second World War. The story of the war is still the story of big countries. Navel-gazing rumbles on in Germany about whether the country was defeated or liberated in May 1945. Modern Russia claims that the bravery and sacrifice shown by the “Soviet people” (a curious term) in defeating Hitler gives the Kremlin a particular role in policing Europe against anything it describes as “fascism.”

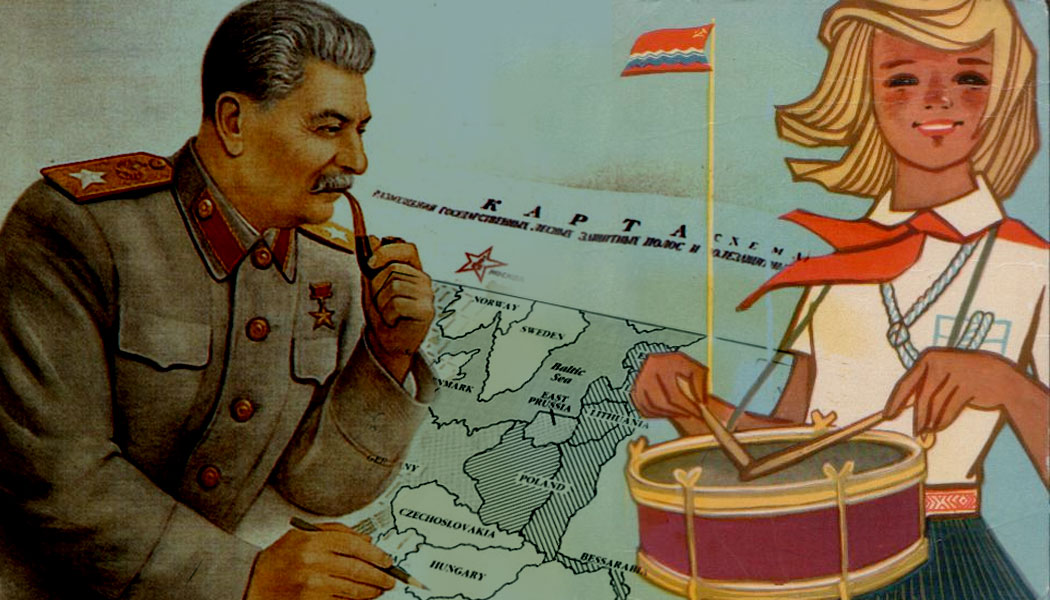

Stalin was a co-conspirator with Hitler and would have happily continued the alliance had the German leader not attacked in 1941.

Both these ideas are questionable. The minority of anti-Nazi Germans was indeed liberated. Later, the Western-occupied zones of Germany became (with a good deal of initial nose-holding) an exemplary democracy. Modern Germans can be glad that happened. But most Germans in 1945 were not anti-Nazi. Even if they did not know (or did not care to know) how bestial the Nazis really were, they would have liked Germany to win the war. Such Germans were defeated. Any failure to acknowledge that bluntly reeks of hypocrisy and evasion.

Russia’s mythmaking about the war is even more obnoxious. The Soviet leadership behaved abominably before, during and after the war.

Stalin was a co-conspirator with Hitler and would have happily continued the alliance had the German leader not attacked in 1941. When the war started, Russia was spared the biggest human and physical costs, which were born by non-Russians. After the war, Soviet rule enslaved the people it claimed to have liberated.

(I should add here that British selective memory about the war remains disgracefully selective: among the many gaps are hushing up the Soviet massacre of Polish officers at Katyn, and the post-war deportation of Cossacks and anti-communist Yugoslavs to death at Stalin’s hands.)

Instead of using the anniversary to obsess yet again about their own history, the big countries should take this opportunity to think about the war from the point of view of the people they consigned to torment between the Nazi hammer and the Soviet anvil. Such thoughts are unsettling. The story of the “good war” is comforting and simple. But in truth the Second World War was not a simple fight between right and wrong. It had many sides, and within those sides many complexities. How many modern Britons would be able to explain (let alone justify) why the UK declared war on Finland in 1941, for example, whereas the United States did not?

Plenty of compensation is still sorely overdue (examples include Germany’s forced loan extracted from occupied Greece and never repaid, and Soviet war plunder that has never been returned to countries such as Estonia). But words matter even more. The anniversary offers an opportunity for a concerted effort to rebut the myths peddled by Russia (that anyone who fought against the Soviet Union was a “fascist”) and also the lingering canard that the German-run prison and killing facilities in occupied territory were “Polish camps.” Germans above all are well placed to say such things, and should do so loudly and clearly.

Reproduced from here with the kind permission of the author and CEPA

A heartfelt “thank you,” Mr. Lucas, from a Polish American whose parents suffered under both the Nazi and Soviet occupations. And now, history is still being rewritten to protect the guilty.