President Ilves Toomas Hendrik Ilves has put Estonia on the map.

For a country the size of Estonia, with a population of just over 1m, this is not just a matter of national branding.

It is a matter of national security.

Estonia is a front line state of the European Union and NATO, a bastion of Western values, a shining post-1991 success story, the epitome of integration.

Toomas Hendrik Ilves has been both a general and a foot soldier in this war. Every Estonian should be grateful to him for his leadership and his efforts.

It’s a member of every important Western club. And uniquely, it is the only country which meets all the rules and standards of all the clubs it belongs to.

Its enemy is obscurity.

Obscurity breeds apathy, complacency and neglect. Put crudely, if you don’t know WHERE Estonia is, and you don’t care WHAT Estonia is, then you are less likely to see WHY Estonia matters. That makes it easier for Russia to subvert and isolate Estonia.

Toomas Hendrik Ilves has been both a general and a foot soldier in this war. Every Estonian should be grateful to him for his leadership and his efforts.

His success is all the greater because he is not the prime minister. He cannot give orders, spend money or assemble big teams of decision makers. His role is ceremonial. His only real assets are words – both spoken words from his many eloquent speeches, and written words, particularly his e-mails and tweets.

It is worth reflecting on the size of his achievement. Even among those who specialise in European politics, I doubt that many people know the name of the presidents of Greece, of Hungary, of Italy, of Portugal, or of Switzerland. These are much bigger countries by population, by GDP, by area. They have world-famous industries and huge cultural resources. They are household names. Estonia wasn’t. But now—increasingly—thanks to President Ilves it is.

He brings formidable assets to this fight. He is an exceptionally hard worker.

I first came across him in the very early 1990s, when I was living in the Baltic states and we exchanged views on the long-forgotten Balt-L news server. He was writing under a pseudonym. For months I wondered who this eloquent, erudite person was, who wrote so ably to me about history, literature, politics and national identity. He never seemed to sleep.

He is a notable wordsmith too. In an earlier life he was a highly proficient journalist—running the Estonian service of RFE/RL. Even now, if I discuss editorial questions with him, I always feel he could be doing my job at the Economist rather better than me. He writes fast and sharply, with an unerring eye for the news hook, the headline and the punchline. As I have told him many times, if he ever needs a job, we should talk.

…he also makes sure that nobody sees Estonia just as a Western garrison state, the last friendly house before you reach the murky lands of Mordor.

But his talents go well beyond journalism.

President Ilves is a former academic. His erudition extends well beyond his first field of study, psychology. He knows Latin and classical civilisation. With little or no prompting he will quote the giants of Western philosophy, from Hume to Habermas, from Aristotle to Žižek. He knows world literature. He also—and this is highly unusual for someone of his generation—has a strong background in computing. I think it is true to say that he is the only head of state, anywhere in the world, who can write computer code. He can fix laptops too.

His practical streak is a formidable asset.

I well remember when George W Bush visited Tallinn. These state visits offer only rather a brief chance for the host to connect with his visitor. President Ilves homed in on President Bush’s great enthusiasm: cutting brush at his ranch in Texas. Within minutes they were engaged in a lively debate about the merits of the Husqvarna brush cutter and its different attachments. If the Russians were bugging that conversation, I hope it truly bemused them. What secret NATO equipment do these codewords relate to?

I well remember when George W Bush visited Tallinn. These state visits offer only rather a brief chance for the host to connect with his visitor. President Ilves homed in on President Bush’s great enthusiasm: cutting brush at his ranch in Texas. Within minutes they were engaged in a lively debate about the merits of the Husqvarna brush cutter and its different attachments. If the Russians were bugging that conversation, I hope it truly bemused them. What secret NATO equipment do these codewords relate to?

President Ilves greatest grasp, however, is of history and geography. He knows these not from books and atlases, but from real life. His family has lived the 20th century, as war refugees in Sweden, where he was born, to émigré life in the United States.

He knows the scale of Estonia’s achievement in regaining its independence, and in anchoring its sovereignty in the multilateral frameworks of NATO and the European Union. He also knows the daunting scale of the problem we all face if that multilateral framework breaks down. Just as his predecessor Lennart Meri, he has sounded alarm calls about the threat from the east long before it became fashionable. Anyone who is now talking with alarm about a “new cold war” wasn’t paying attention.

Of course Toomas Hendrik Ilves was not always president—though it may seem like that to the younger people at this dinner. He also served his country as Ambassador to the United States, and twice as foreign minister.

He was an exceptional success in these roles—in Washington DC, for example, he single-handledly ensured that Estonia was able to establish its embassy in a prime downtown location, against what seemed like implacable opposition of the local residents, who did not want yet another diplomatic building in the neighbourhood, with all the security and traffic issues it brings. Ambassador Ilves overcame those difficulties with a mixture of guile, firmness and persuasion which will benefit Estonia for decades to come. I know it is one of his proudest achievements.

But I still hesitate to call him a diplomat— because at heart he is not very diplomatic. He is impatient and informal. He dislikes ceremony, bureaucracy and protocol—confounding other embassies’ security by turning up to receptions in his own car. They thought he was the driver, and looked in vain for an ambassador in the back seat.

That approach is unusual—but commendable. Just as the top jobs in politics should go to people who don’t really like politics, the top jobs in diplomacy should go to people who don’t really like diplomacy. They do these jobs because they want to serve their country, not to make a career.

And of course he has been a politician too. He has tasted crushing defeat as well as triumph. He was an exceptionally important member of the European Parliament for Estonia, in the first cohort of new MEPs who joined along with their countries. He has not a starry-eyed Europhile. But he sees very clearly how vital it is for Estonia to be at the table when decisions are made.

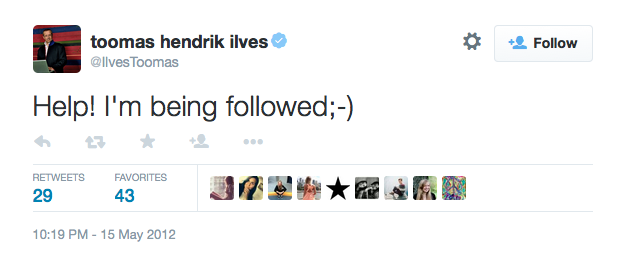

But I want to conclude with his role as Estonia’s CIW, its chief information warrior. If tweeting was an Olympic sport, Toomas would be in the national team—and Estonia would win a gold medal.

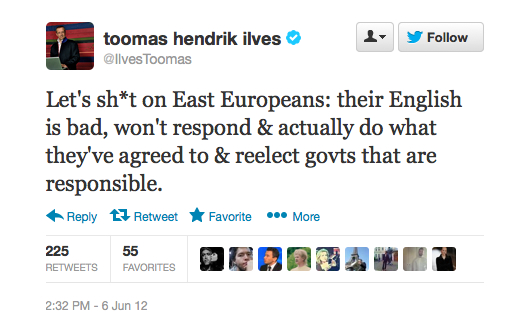

He plays both offence and defence. He mounted a successful campaign against the use of the anachronistic and pejorative term “eastern Europe”. He defended Estonia against all attempts to distort or overlook its historical perspective. He understands that the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact remains modern Europe’s original sin, and that any attempt to relativise or justify it is a direct threat to the national security of all the countries it affected.

But he also makes sure that nobody sees Estonia just as a Western garrison state, the last friendly house before you reach the murky lands of Mordor. He has pioneered the idea of E-stonia, with E as in e-commerce, e-banking and most of all e-government. Perhaps more than some Estonians themselves, he grasps the importance of strong cryptographically based identity as a platform for our interaction with each other, with businesses and with governments. If you haven’t already applied for e-residency, please do so now.

I should also say a thank-you at this point. It is thanks to President Ilves, my friend Toomas, that I am Estonia’s e-resident 0001. Along with Lithuanian visa 0001, gaining this was perhaps the proudest moment of my professional life.

I am sorry to say that the e in e-stonia sometimes seems to stand for something less pleasant: envy. I have been horrified by the prurient, inaccurate and unfair treatment that my friend has received in parts of the Estonian media in recent times.

But if it is any consolation, Lennart Meri, Estonia’s first post-1991 president, attracted similarly unfair sniping in his last years in office—unpunctual, eccentric, extravagant, careless—although he is now rightly revered as one of the country’s founding fathers.

I do wonder if Estonians ever reflect on what signal this sends to other able, patriotic people contemplating a career in politics. Estonia’s head of state is not elected as the patron saint. He (and now she) is a real person. As Shakespeare might have written,

Hath not a president hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us do we not laugh?

I know that Toomas is feeling more wounded than tickled right now. But he should remember that he also has very many friends. Dear Toomas, Dear Mr President. We are proud of you, grateful for your friendship, and delighted that you are here among us to receive this honour.

The above remarks were delivered by Edward Lucas at the Warsaw Security Forum, October 2016 and are republished here with his permission.