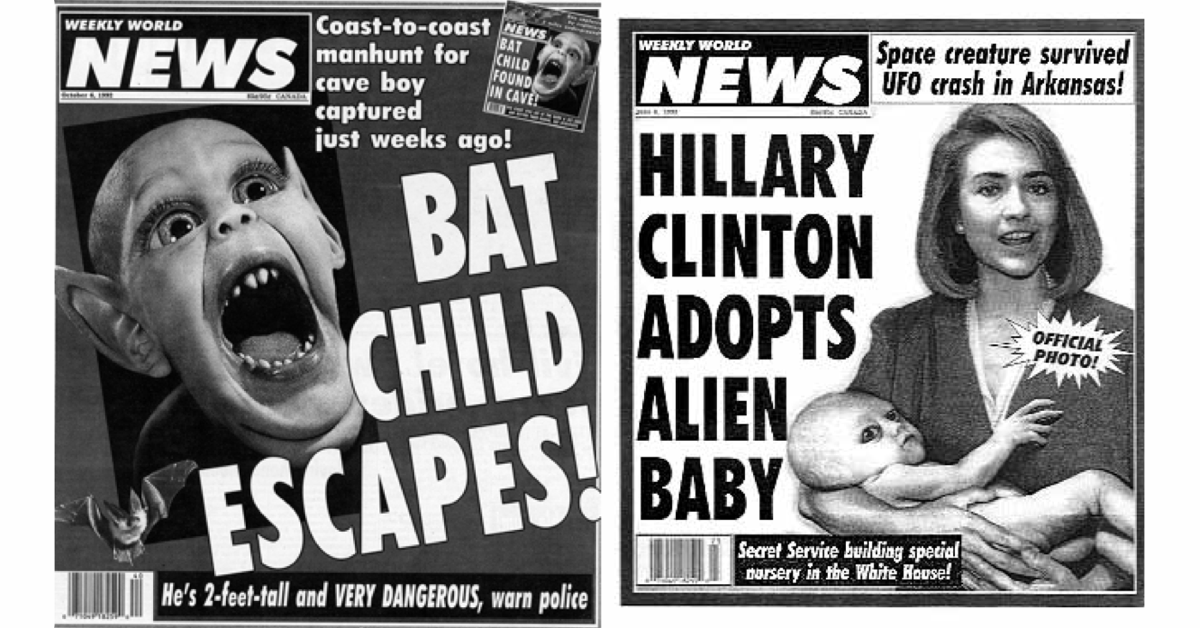

There has been so much talk about “fake news” and information warfare lately that both terms are becoming over inflated, used so liberally that they become devoid of meaning. Different sides in political and ideological battles now routinely accuse each other of spreading fake news. Not least in the dialogue between liberals and conservatives in the aftermath of the emotional presidential elections in the United States, where now, the president-elect calls CNN “fake news” (unless, of course, this quotation is fake news itself – it’s becoming very hard to know!).

The news and opinions that are not the only battlefields in this verbal war, it is also being waged among the names and titles of institutions and NGOs – here in Finland there are battles going on about who can call themselves anti-Fascists, human rights activists, and now among those who are researchers of hybrid threats. Information warfare, described a few years back as hostile attempts by certain state-sponsored agents to influence international public opinion in biased, propagandist and deceitful manner, has become a Hobbesian war of everyone against everyone. We all seem to have become information warriors in a jungle of words.

Information warfare is actually not new, it was called propaganda during the Cold War. Now its intrusive existence has just become more widely acknowledged, by top politicians as well as international media. What has also changed is the speed at which information, including fake information, travels around the world. It is possible to stir up a lot of trouble with fake news before its fakeness is revealed, and any rebuttal will never connect with as wide an audience than the fake news did in the first place.

It becomes even harder to tell fact from fiction, if we start identifying as “fake news” any statements that we find ideologically disagreeable or that come from a political opponent.

The most troubling thing about this mess of fake, semi-fake, biased and downright deceitful information, is that it is becoming increasingly hard to detect when even the basic factual information we get through media may or may not be reliable. It is becoming harder to know when we just disagree with someone about their politics, opinions and judgments, and when we are dealing with plain lies and made-up stories.

In this situation, the role of traditional media has not disappeared, but it has changed: they have become a quality filter, a certificate that a piece of information they distribute is true. We look at the headlines on our timelines, and then immediately check who is publishing them: serious media offers credibility to the factual contents of the piece. This, for them, implies an enormous burden of responsibility.

There are many kinds of information aggression, from biased emphasis and selective revelation of facts to exaggerations, from judgmental and stereotypical opinions to direct lies. I grew up in the Soviet Union, which means that we learned early on to detect propagandistic tone in the media and fish the facts from a sea of exaggerated judgments. This “educational” background is actually useful in today’s world.

Judgments, even when harsh and unfair, constitute the easiest part of the battlefield: they do not pretend to be anything but opinions, and when expressed in an ugly and abusive manner, they reveal more about the speaker than the object of her abuse. In contrast, facing direct lies, even the most critical reader or viewer is helpless. In the West we do not expect to be lied to by the press. This is where fake news is most dangerous, especially when it comes from sources that we believe we can rely on.

It becomes even harder to tell fact from fiction, if we start identifying as “fake news” any statements that we find ideologically disagreeable or that come from a political opponent. Therefore it is important to call a piece of information “fake” only when it really is fake, false, non-news. We should not label all political disputes “fake news”.

What happens to freedom of speech, as we become more and more confused about fact and fiction in the news? It is unpleasant to see endless amounts of falsehoods or semi-falsehoods or vile hate speech circling around the global info-sphere. But banning unpleasant speech is a slippery slope: who has the right to tell us when exaggeration or ideological pathos is damaging enough for the speech to be classified as criminal?

Europe has responded to increasing online noise levels by legislating new hate speech laws. Two European MPs, Geert Wilders of the Netherlands and Teuvo Hakkarainen of Finland, have recently been convicted of hate speech. This is a dubious approach. Verbal abuse is unpleasant, but it hardly ever is seen as anything but a subjective judgment of the abuser. Leaking sensitive information or telling lies can be much more damaging than impolite statements about people of groups. It is lies and leaks rather than ugly language that can actually damage lives and affect political realities.

In fact it seems that criminalising hate speech feeds fake news sites that grab the opportunity to identify themselves as “alternative media”; as the only ones “brave enough” and who dare to “tell the forbidden truth”. Acquiring a martyr status helps them sustain that image.

Some defenders of free speech have insisted that freedom of speech also protect lies – because people err, erring is human, and if making mistakes becomes too costly, freedom of expression is inhibited. I prefer a Millian liberal approach – free speech should be protected unless it causes direct harm, through libelous defamation of a person’s reputation or incitement to violence (which, obviously, includes threats). But banning vaguely defined “hate speech” opens up a slippery slope toward censorship.

However, freedom of speech also includes the right to gain information. If anything goes in public discussion and no media bear any responsibility for what they say to be true, the information anarchy that follows leads to a situation where it becomes impossible to gain any reliable information at all. Therefore, at least the serious media whose role is to filter credibility, should take fact checking very seriously – and visibly correct the false claims that they eventually do publish by mistake.

I have personally suffered the consequences of reputation-damaging libel. My career with the state of Estonia abruptly ended after a massive, deliberate and totally fictional slander campaign by the Estonian media – including so-called mainstream media, apparently in cooperation with some political insiders. As the editors of the libelous papers refused to correct the damaging claims they knew to be false, it became impossible for me to ever take anything published in those media seriously again. Once they lie about something you know to be false, you never know if they are telling the truth about things that you have no personal experience about.

This is, at worst, what may be happening with media credibility on a larger scale right now. Due to my experience, I no longer can subscribe to simplifying claims that information warfare is something driven only by pro-Kremlin trolls, more or less official information factories of certain undemocratic states, or marginal, extremist bloggers. Those trolls do exist and they are still active, no doubt, but unfortunately, the “good guys” do it too, democratic politicians and free mainstream media in free countries also engage in “trolling”. Indeed if we treat information warfare as a weapon of some political actors while others are considered pure by default, it becomes a label by which established elites can beat their political opponents.

The reality is not so black-and-white. I still assume that international quality media do not publish plain lies as quickly as more easily influenced media can do in small countries. But we should be aware that the blurring of the lines between serious and fake media is more and more frequently missed by the serious media as well, as we have seen in connection with the US Presidential election campaign, and its aftermath.

And still I remain a strong supporter of the US First Amendment. I believe it is high time we create our own version of it in Europe. Public speakers should be held responsible for libel and incitement to violence, but their audiences should be treated as grown-up enough to judge the quality of unflattering judgments by themselves. The best protection against ideological bias and bad style is an alert, critical consumer with a strong sense of media literacy. Without our own “First Amendment” in Europe, references to fake news, hate speech and infowars can be increasingly used as a means to silence those whose speech the powers-to-be might be tempted to stifle for other reasons than sincere pursuit of truth.