When people in Moscow or the West talk about “nationality problems” in Russia, they typically focus on ethnic groups which, because of their large size, activism or political utility, have the status of republics or other state formations like the Tatars, the Buryats or the Chechens.

But one of the most serious nationality problems for Moscow today involves the large number of small groups lacking that status but having another one: the numerically small indigenous peoples of the Far North, Siberia, and the Far East, groups who despite their size are increasingly a problem because of the natural resources in the places where they live.

In some ways, this is a problem of Moscow’s own making: it has created a status which at least in principle gives these peoples greater ability to defend themselves against the demands of the state and of those who want to develop the natural resources and now finds itself forced to move against groups it had earlier employed as advertisements of its solicitousness.

Two new articles highlight these tensions: one by Moscow State University ethnographer Dmitry Funk who talks about the ways in which this status has evolved and is now being used and a second in “Novaya gazeta” about Moscow’s heavy-handed use of the foreign agent law to move against these groups.

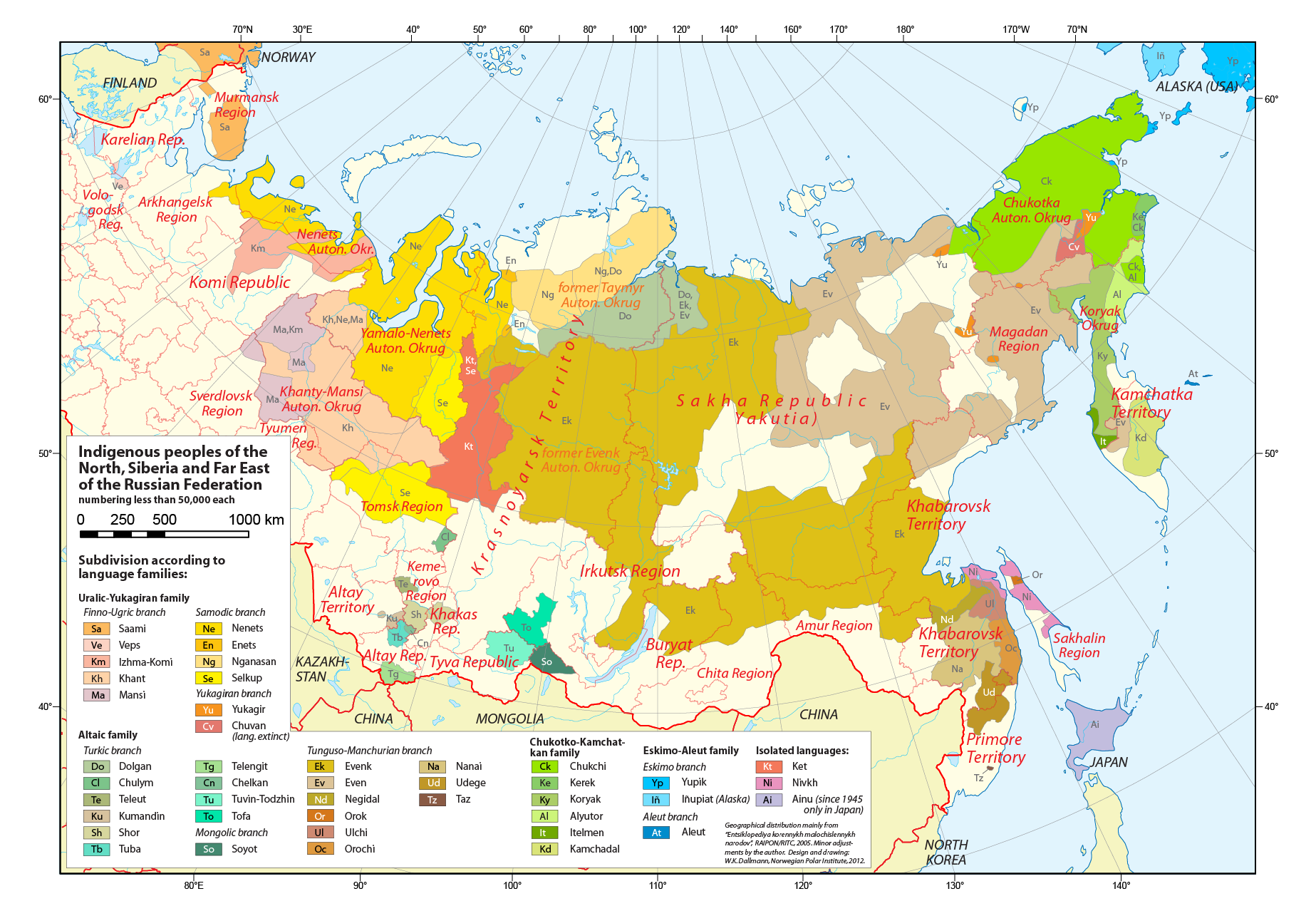

Russians have long referred to the peoples of the North, but the category “numerically small indigenous peoples of the Far North, Siberia and the Far East” arose at the beginning of the Soviet period and included some 50 different peoples, most of whom were engaged in traditional economic activity the Bolsheviks viewed as distinct and primitive, Funk says.

For most of the Soviet period, this group of peoples was considered “a special accounting category” more than one whose members should be given special privileges, and by the 1960s and 1970s, it had a stable membership of 26 peoples, who although they suffered from alcoholism and other social diseases were viewed as being on course to assimilate to Russians.

the current Russian government seems to be far more inclined to try to suppress any activism by these groups lest they get in the way of its economic exploitation of the lands on which they live

But at the end of the 1980s, Funk continues, “it suddenly turned out that [these] 26 peoples had not fallen asleep, forgotten their languages, lost their cultures, and even if something had happened, they nonetheless wanted to restore, reconstruct and use them in their contemporary life.”

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Moscow scholar says, this category took on “a second life: in it were included certain peoples of Southern Siberia and thus there were now not 26 but 30 [such] peoples. [And] then gradually in the course of the 1990s and early 2000s, this group expanded and expanded and today it includes on the order of 40-45 ethnic groups.”

To qualify for membership, a people had to number fewer than 50,000, “be located on the territory of its ancestors, be involved in traditional economic activities, and maintain its traditional culture and language,” the Moscow ethnographer says. It is not enough to have a self-designator, “but you must consider yourself a separate people.”

The situation is complicated, and appended to Funk’s article is a discussion of the problems Russian scholars and officials have had in defining national minorities, indigenous peoples, and related issues, problems that are inherently controversial politically.

Funk gives the case of the Altays as an example of such problems. The Altays as a group “are not included in the list of numerically small indigenous peoples. And for a long time in Soviet ethnography and Soviet scholarship it was considered that they were a single people, formed to be sure of various groups but having become a single socialist nationality.”

But at the end of Soviet times, “it turned out that whose who were listed as Altays still remembered that they were not completely Altays.” And “thus appeared on the map of the Altay Republic and on the ethnographic map new ethnic groups: the Chelkans, the Tubalars, the Kumandins, the genuinely Altays, and the Telegits.”

Some of these groups were successful in being classified as part of the numerically small indigenous peoples of the North, Funk says, despite the fact that officials in the Altay Republic “very much feared” that that state formation would be suppressed and they lose their jobs if all these peoples declared their identities as separate from the titular one.

According to Funk, “everything turned out fine” but only because in Russia “there is no direct correlation between the titular ethnic group and the status of the formation in which it lives. That can be a republic, an autonomous district or something else.”

There are good reasons why small ethnic groups should want to be on this list, the Moscow scholar points out. They not only acquire special benefits and subsidies, but they also acquire an enhanced ability to defend themselves and their way of life against outsiders, one far greater than the ethnic Russians who live among them and may live in much the same way.

“If you aren’t included in this list,” he continues, “then you will be dealt with in the same way the authorities deal with all other citizens of the Russian Federation. Then you will not have additional levers to defend the territory on which you and your ancestors lived, hunted, caught fish, and carried out your traditional way of life.”

Moreover, “if you do not have the chance to defend this land in this additional way, then various kinds of complex life situations can occur” as “it is no secret that the territories where the small indigenous peoples of the North life are rich in natural resources” including but not limited to “gold, uranium, mercury, oil, gas and coal.”

And “if you are not in this list … then you will find it much more complicated to defend your land and rights to the way of life you want to lead. This is important to preserve your culture because if you do not have a territory where you live in a compact way, then it will be very difficult to guarantee that your children will study their native language and maintain traditional values.”

Of course, Funk says, “this does not mean that the people will disappear,” but it does mean that those who don’t get on the list will be at far greater risk of losing their language and national distinctiveness. Indeed, “throughout Siberia, an enormous number of the peoples of the North have already lost their languages, but this doesn’t mean they don’t speak any language.”

In some places, they are acquiring the language of larger groups nearby such as Sakha; but in many, it means they are going over to Russian. “Nevertheless,” Funk continues, “people are preserving their ethnic identity, want it to develop into the future, and being on the list [of numerically small indigenous peoples] gives them this opportunity.”

The Moscow ethnographer concludes his discussion by noting that there has been one development that few anticipated: in many cases, members of the younger generation of such people speak Russian rather than their national languages and do not engage in traditional economic activities. But they still identify as members of these groups, especially if they are on the list.

What has appeared, Funk suggests, may perhaps best be called “a stratum identity,” much like the ones that existed in tsarist times. The current government of the Russian Federation must take this development into account as it deals both with the individual peoples of the region and with the combined membership of this category.

But as Tatyana Britskaya, who covers the Far North for Moscow’s “Novaya gazeta” newspaper, points out, the current Russian government seems to be far more inclined to try to suppress any activism by these groups lest they get in the way of its economic exploitation of the lands on which they live than to take their concerns into account.

The Moscow journalist describes the way in which the Russian justice ministry has declared the Batani Foundation for the Development of the Numerically Small Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East a foreign agent even though it has not investigated the group and even though the group has received no foreign funding.

Pavel Sulyandziga, the foundation’s head, says he learned about this action from the website of the justice ministry which declared that officials had decided that his group is a foreign agent within the meaning of Russian law on the basis of “an investigation carried out” by the justice ministry.”

He suggests that this Moscow action reflects clashes between the interests of Russian companies seeking to develop the North and the interests of the peoples of the North. “The root of the contradiction is the issue of strengthening the rights of numerically small indigenous peoples” to engage in their traditional forms of economic activity.

Moscow has moved against other groups linking together the numerically small peoples of the North before with the justice ministry declaring that the association of 41 of these peoples was in violation of the law. Sulyandziga said he had not been able to reverse that decision, but the association nonetheless a year later “renewed its activities.”

“Now,” Britskaya says, the activist intends to challenge the inclusion of his foundation in the list of foreign agents in court – as soon as he “receives official notification” that it is on that list from the Russian justice ministry.

_Lofting-1.jpg)