During my years at school, maps hung on our classroom walls on which the Finnish borders were clear, as were those of the Soviet Union; Estonia however, did not appear on the map. A country that is not marked on a map does not exist by the way – be the reason for its absence what it may. It’s difficult to talk about this kind of a nation with people who don’t know it, as well as much about the injustices and threats experienced by the people of that country. It’s difficult to prove the existence of such a nation since it cannot be pointed out on a map hanging on a classroom wall, printed in a school textbook or newspaper, nor can its flag be shown. Maps however, leave a strong, visual imprint in the memory, which is far-reaching.

The same maps were used in our neighbouring countries and the Soviet Union – the kind which did not include Estonia or the other Baltic countries. I remember the bewilderment experienced in the mid 1990’s, when our geography teacher began drawing new borders in the old textbooks we were still using and asked students to do the same. Finnish youth were already aware of the independence of the Baltic countries, but redrawing the borders of the Balkan countries did not cause any noticeable interest, even though marking up school books in such a way was something we had never been done during our time at school. The lack of enthusiasm stemmed from the fact that we had to learn new and complicated names, but we were not told why we had to learn these new borders and how they had developed. This was once again due to the fact that during our time at school, Yugoslavia had been viewed in Finland through a Soviet prism.

Yugoslavia had been a clear and simple concept for students. There was no notion of the new countries, nor did anyone know about the war, the perpetrators of which were clear to only a few. Without such a notion, learning and remembering is difficult. The fact that the geography teacher did redraw the borders was quite vivacious, since geography class was the only one where these matters were discussed during my time at school.

I can imagine that there have been similar reactions elsewhere and perhaps this is why the Balkans and Baltics continue to be mixed up from time to time; more often the further afield you go, but it happens in the Nordic countries as well.

In addition to on maps, the Soviet narrative also dominated in school textbooks. Familiar Soviet tales of how the Soviet army “liberated” the Baltic states and how the peace-loving Soviet Union has not fought once since World War II, were repeated in Finlandized school books in Finland. The war in Afghanistan, which claimed so many lives, was considered to be a “problem”, yet the war in Vietnam was critiqued at length. Finlandization in school textbooks can clearly be seen for instance, when compared to the way in which the Soviet Union and the U.S. were presented in the series of books “History and us”. There, the Soviet Union was presented using huge diagram showing the growth of industrial production and the United States was presented via diagrams showing how violent crime was growing in its large cities. The U.S.’s poverty, drug problems and other acts of fear were given much print, while in the Soviet Union everything was beautiful and blooming.

Some Finns did visit Tallinn, Vyborg, St. Petersburg and Moscow, and saw a little with their own eyes; some teachers taught concepts that were beyond the official books. One Finnish librarian secretly collected books at home which had been taken off the library list, because they were considered Anti-Soviet and were to be destroyed. I’m sure such secret home libraries had their share of readers.

Stories told by regular people, bore holes into the Iron Curtain, but the majority of people living in the West had never actually seen what was truly behind Soviet propaganda. They accepted what they remembered from school books, read in the paper and saw on TV as the truth. Those, who managed to enter the Soviet Union only saw places that foreign eyes were allowed to see and lived in hotels intended for foreigners.

These politics were propagated with campaigns supported by the Kremlin, which are also familiar in Estonia: Soviet nostalgia is restored and political symbols are manipulated with. If the West had considered Russia a colonial state, the warning signs would have been seen.

The period of imperialism of Western countries was however, thoroughly covered in school. The word “imperialism” was never associated with the Soviet Union and was not even associated with Russia following the collapse of the Union, Bronze (Soldier) Night or the war in Georgia. Instead, expressions such as Russia’s or the Soviet Union’s “sphere of influence” and “area of privilege” are still placidly used in the Finnish media’s lexicon and school lessons where the Baltic and Eastern European states can still sometimes be referred to as “buffer states”.

The treatment of colonies or former mother countries is not considered part of this rhetoric in connection with Russia or the Soviet Union, even though these concepts apply to the Soviet Union’s activities based on oppression, stealing of possessions and activities based on slave labour, as well as Russia’s new goals.

Only recently, in connection with the war in Ukraine, has the media of some Western countries begun using vocabulary alluding to imperialism when referring to Russia. In a seemingly ashamed manner, but nonetheless. The word has appeared in editorials and the texts of visiting columnists. It is therefore a subjective definition. It is seen as not yet belonging to fact-based language use or the neutral language of the news. Yet – it is a start.

One of the reasons for the success of Russia, is that the West is not used to associating imperialism with Russia, regardless of the fact that the Soviet Union’s wealth was based on stealing possessions and slave labour, and half of the countries in Europe were colonies of the Eastern mother country for a long while. The prevalent thinking in the West was that imperialism has to do with the past of the United States and Western Europe, and colonies were seen as being something incredibly far, something associated with people whose skin colour is not white. Therefore, the Soviet Union’s propaganda was effective: its props, which showed the Union as the cradle of the voluntary friendship of nations was accepted as true.

Using classic game tactics, Russia accused the U.S. of imperialism for years; sent messages via multiple channels rife with positive adjectives describing the Soviet Union, thereby dispelling any doubts cast against it. Since the notion of imperialism was focused on the U.S., the same word cannot therefore logically be used to describe the Soviet Union. Through its lengthy efforts, Russia succeeded in making the myths supporting its position seem natural.

Soviet Anti-Western Propaganda

Many former colonial countries have moved in the completely opposite direction. France and Great Britain cannot intervene in the writing of the history of former colonies. Their intrusion into the affairs of former colonies is not looked well upon, except for when there is an attempt to amend destructive actions of the past. Thanks to this development, the situation of former mother countries, as well as of the situation of oppressed groups of people has changed considerably. Post-colonialism has made power structures visible. Also deserving praise for this development are the womens’ movement, anti-racist activities and post-colonial awareness of the fact that language is a tool for power which influences reality.

Laws are insufficient – equality cannot develop if language creates inequality and supports systems where the voice of the subjugated cannot be heard.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, when times and the political situation changed, the eradication of the traces left by Soviet propaganda became topical in Estonia. It was necessary to begin using expressions which would correspond to people’s actual experiences. People began discussing the occupation, deportations and mass murders – things which, according to Soviet propaganda, had not occurred. The West did not apply the same kind of corrections to the Soviet narrative. The former colonial empires of the West had by then reached a time when people were aware of their exploitation of former colonies; it was admitted and was discussed, but the Soviet narrative was not unravelled in similar fashion.

Russia, the mother country of the former Soviet empire never reached a level where these narratives would have been broken. The opposite is true. For quite a while, Russia has attempted prohibiting former colonies from writing their own history and does so using the narrative of Soviet propaganda. This means denying facts such as occupations, deportations and mass murders. In this way, belonging to Russia’s so-called sphere of influence by former subordinates is shown as being natural. The goal is to keep former colonies in a power hold, to create confusion in the West and create opposition to revealing Russia’s war crimes.

Throughout its existence, the Soviet Union has engaged in active distribution of disinformation and the manipulation of western public opinion in the West. As a result, half of Europe’s history has been viewed through a Soviet prism for half a century. This shaped the direction of how people in the West got used to speaking of the Soviet Union, as well as its legal successor Russia. In the West, Russia was not used to being seen as an imperialist country, that is why the core of that state’s activity – expansion, remained undiscovered. Also the fact that the same expansive activity also influenced Western thought from the East and continues to do so.

Russia’s imperialism also remained unnoticed because other former empires such as France, Great Britain and even Belgium, moved in a totally different direction and no one in the West could imagine that any country would like to move to a place which the West considers the past, not modern and out of date. This is, once again, a lack of imagination.

According to Russian-American editor and writer Masha Gessen, the popularity of both Trump and Putin have come as a surprise to the West because we were not capable of imagining anything like it. For years, Gessen tried to warn Western opinion leaders, editors and politicians of the threats, towards which Putin is leading Russia and the world. She has evidence of it. Putin’s deeds and words are exactly those, of which Gessen spoke.

Simultaneously Putin himself offered the West additional material evidence. Journalists and activists were murdered, free speech was limited, election results were rendered null. Still, even Russians could not believe that Putin could be as bad as Gessen claimed. The problem was therefore not in a lack of material evidence, but in the fact that people could not imagine the kind of future, of which Gessen spoke. For facts and evidence to lead people to an understanding of what is happening, logic is not sufficient.

That’s why the ability to imagine what these facts and material evidence mean must be supported. They must be supported with images, and this brings us back to words. Expressions must be used, which people both here and elsewhere already understand. That is why it is important to talk about colonialism and use vocabulary associated with it. These expressions bring forth emotional reactions similar to reflexes, the ones which Russia uses for psychological manipulation. These expressions are related to negative feelings, and therefore Russia attempts to keep them away from narratives it is associated with and does so successfully.

The war in Ukraine came as a surprise to the West, but Moscow had prepared for it since the orange revolution. Colonialism was hidden behind the politics of compatriots, behind the fact that the rights of Russian culture and Russian-speakers are being protected in border countries. These politics were propagated with campaigns supported by the Kremlin, which are also familiar in Estonia: Soviet nostalgia is restored and political symbols are manipulated with. If the West had considered Russia a colonial state, the warning signs would have been seen.

If Great Britain suddenly began to restore and glorify the splendour of the British empire in Ireland, a strong international reaction would follow. If independent opinion polls were to suddenly reveal that Germans consider Hitler to be the most important figure in its history, the international public would be shocked and Germany would immediately be considered dangerous. Russia has acted in this way regarding Stalin, and even though news of this was considered to be strange, they were not considered to be appalling, nor was the new direction broadly condemned.

First of all: no one in the West thought that such activity could influence the West itself. It was considered the quirk of a far-off and unknown country and no one knew how to react in a timely manner to the fact that Russia supports the larger part of Europe’s radical right-wing parties.

This is one example of how far-reaching the effect of propaganda and the manufacturing of a psychological atmosphere can be. Its traces remain in the language and in memory for decades. The Soviet Union left a fertile ground from which it was easy for Russia to continue psychological influencing. Getting caught up in the cold war era rhetoric of privilege prevented people from seeing Russia’s expansive activities in all of Europe as well as in the United States. It was forgotten that in the same way that the Soviet Union dealt with protecting communists everywhere, Russia wishes to dominate throughout the world today.

Kremlin Propaganda Channel RT Denies the Estonian and Baltic Genocide

In the West, novels about Russia’s sphere of influence and the idea of historic privilege are not written for the general public. There are no films on the subject, yet there are about colonialism, and a lot in fact, and that is why it is easier to get caught up in a narrative associated with colonialism and to be empathetic towards victims of colonialism. Exploiting the victims of colonialism or belonging to a former mother country is not considered at all natural in the Western world.

It is easier to acknowledge a country’s defence needs and therefore the idea of privileges and buffer countries does not seem like a bad one. It sounds more natural, when privileges and buffer countries are spoken of. The elements of exploitation are dispelled, as is the economic gain, although Estonians know what the world’s largest animal is. It was the Estonian pig, whose feet and head were in Estonia, under the counter, and its carcass is on the counter in Moscow.

The same kind of oppression is not associated with privilege and buffer countries as with colonialism, even though for example Finno-Ugric peoples are held in Russia’s iron grip, because they happen to live on top of great natural resources. This is why ethnic repression can flourish in Russia: the situation of those who are downtrodden interests no one.

Opinions have been expressed in Western countries that the example of Finlandization would fit Ukraine and this has also been considered attractive in some Eastern European countries. The idea of Finlandization lost its appeal elsewhere following the collapse of the Soviet Union, and its political treatment is also an unfinished process.

For this reason, it could seem to be an attractive form for some, but even Finns who supported Finlandization do not suggest this route for Ukraine. Relating positively to Finalandization is supported by Soviet propaganda. That anyone even suggests this form to Eastern European countries is the result of old propaganda.

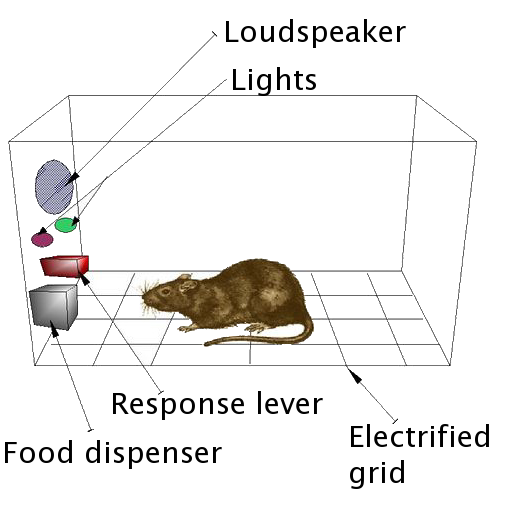

According to the director of the Finnish Institute of International Affairs Mika Aaltola, during the years of Finlandization, Finland was like a rat in a Skinner cage. A Skinner cage is a tool used for subordination, into which a laboratory animal is placed without water or food. It is taught to act in a certain way in order to get a little bit of food and a drop of water. The reward system teaches the rat manners of behaviour. The immediate director of the activity is however the experimenter outside of the cage.

Following the Second World War, Finland thereby found itself in a particular Skinner-like cage of influence. Various rewards rattled from the East, such as the growth of exports and an alleviation of the atmosphere. Finland’s obedience was put to the test with special methods, such as diplomatic note crises. Rewards and punishments were effective hand in hand. For the world at large, Finland was fodder. It was a picture window through which the Soviet Union proved to others that it was capable of calmly existing with a neighbouring country, even though it was actually controlling the situation. Finland was therefore like a example, just like the exemplary state farm in the Soviet Union that they dared present to foreigners.

Since one of the ways Russian psychological influence works is by leading activities in such a way that the one being led reacts in a desired fashion, it can be said that Finlandization was the Soviet Union’s success story. Finland learned to react to provocation with the desired reflexes.

It’s worth recalling, that Finlandization robbed Finland of its ability to write its own official history and independent public opinion of Russia. This also increased censorship, which people supported without realising it, claiming that freedom of speech in critisizing Russia’s politics existed.

Finlandization did and continues to affect how Finns talk about Russia. That is why any kind of criticism regarding Russia’s politics is often considered to be recklessly bold. I find this to be problematic since expressing criticism concerning the activity of a country engaged in expansionist policies should not be considered particularly “bold”. It should be normal, just as normal as criticising the situation of freedom of speech in China. This is not a special situation or marginal opinion, but ordinary: as it should be. Someone criticising China should not hear that s/he is a fascist, provocateur or a “NATO-whore (a term commonly used in Finland)”.

These are expressions which are in use in Finland to describe people who criticise Russia’s actions. People who have, for instance, criticised the United States’ actions in the Guantanamo Bay prison have not been met with similar berating.

If every person who criticises Russia’s actions is sooner or later called a provocateur, fascist or Russophobe, what we hear in this condemnation is the echo and language of Soviet propaganda, by which a situation where it was normal to talk about Russia using only friendly adjectives and the use of negative ones was declared to be abnormal.

All the while Russia’s political rhetoric has hardened. Fictitious schemes, according to which Russia is surrounded by enemies, have been created for years. It has long been normal to speak of nuclear weapons in the Kremlin.

Aleksander J. Motyl of Rutgers University, specialising in Soviet and Russian Studies, has analysed Russia’s public speeches and noticed that recently the tone of political speeches has changed. For instance, mass murders and ethnic cleansing is spoken of in a new light. These are not speculations, but Russia’s usual political discourse. The detailed presentation of these types of intentions has been normalised.

For instance, Russian economist and former official of the Office of the President, Mihhail Hazin, announced that Ukraine should be divided between Poland and Russia. Independent Ukraine would thereby cease to exist. According to his plan, Ukrainian culture and the Ukrainian language should be prohibited in the areas to remain under Russian rule and the country’s northern areas should be transformed into agricultural lands, where the defence forces and industry would be eliminated. He would have the area’s so-called excessive population transported to Russia’s far-East. Since there continue to be millions of people who cannot be “cured”, some of them should be exterminated and another portion sent out of the country.

Of course such rhetoric is a test and is intimidating and thereby a part of Russia’s psychological warfare. It is also the step-by-step progression of the normalisation of violence. In exactly the same way, step-by-step, numerous genocides have been committed in the history of the world. This is how the people of one’s country are slowly made to get used to an idea which in another context would horrify them.

In conclusion I will borrow a line from the U.S. human rights activist and poet Audre Lorde: “Your silence will not protect you”.

From a speech delivered by Sofi Oksanen at the Enn Soosaar Conference in Tallinn. Translated from Estonian by Riina Kindlam who is a Toronto-born freelance translator and writer living in Tallinn, Estonia. She has worked as a translator at the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and contributes regularly to Estonian newspapers abroad.

From a speech delivered by Sofi Oksanen at the Enn Soosaar Conference in Tallinn. Translated from Estonian by Riina Kindlam who is a Toronto-born freelance translator and writer living in Tallinn, Estonia. She has worked as a translator at the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and contributes regularly to Estonian newspapers abroad.

This article clearly answers the question why there was a sugar industry in Latvia during USSR and why we lost our sugar industry in “free” independent country after joining European Union. Also, this article clearly answers why in USSR we had electric power for people, but now electric power industry is a instrument to remove our money and patch holes in the state budget. This article clearly answers why apartment heating in USSR was for heating apartments, but now it is for get rich for a few. Etc.